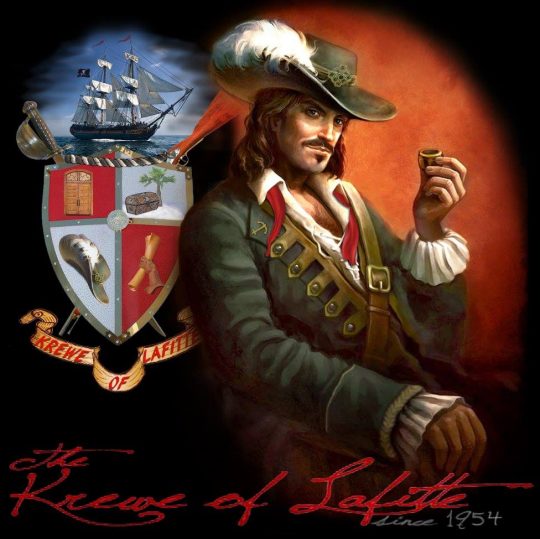

Jean Lafitte

…The Pirate Patriot

In the early 19th century, the Gulf of Mexico was a hotbed of piracy and privateering, and among the most notorious figures was Jean Lafitte. Born around 1780, Lafitte was a Frenchman who found his calling on the high seas. He and his brother Pierre established a base on Barataria Bay, near New Orleans, where they ran a thriving smuggling operation.

Lafitte was more than just a pirate; he was a cunning businessman and a master of diplomacy. His fleet of ships was a formidable force, and he commanded the loyalty of hundreds of men. Despite his illicit activities, Lafitte was well-liked by the local population, who benefited from the goods he smuggled into the region.

In 1814, as the War of 1812 raged on, the British sought Lafitte’s aid in their campaign against the United States. They offered him money and land, but Lafitte had other plans. He informed the American authorities of the British proposal and offered his services to General Andrew Jackson. Initially skeptical, Jackson eventually accepted Lafitte’s help, recognizing the strategic advantage of his knowledge and resources.

Lafitte and his men played a crucial role in the Battle of New Orleans, providing much-needed artillery and manpower. Their efforts helped secure a decisive victory for the Americans, and Lafitte was hailed as a hero. Despite his contributions, Lafitte’s piratical ways continued, and he eventually moved his operations to Galveston Island, Texas.

Jean Lafitte’s legacy is a complex one. He was a pirate, a patriot, and a man of many contradictions. His story is a testament to the turbulent times in which he lived and the indomitable spirit of a man who navigated the treacherous waters of both the Gulf of Mexico and the shifting allegiances of war.